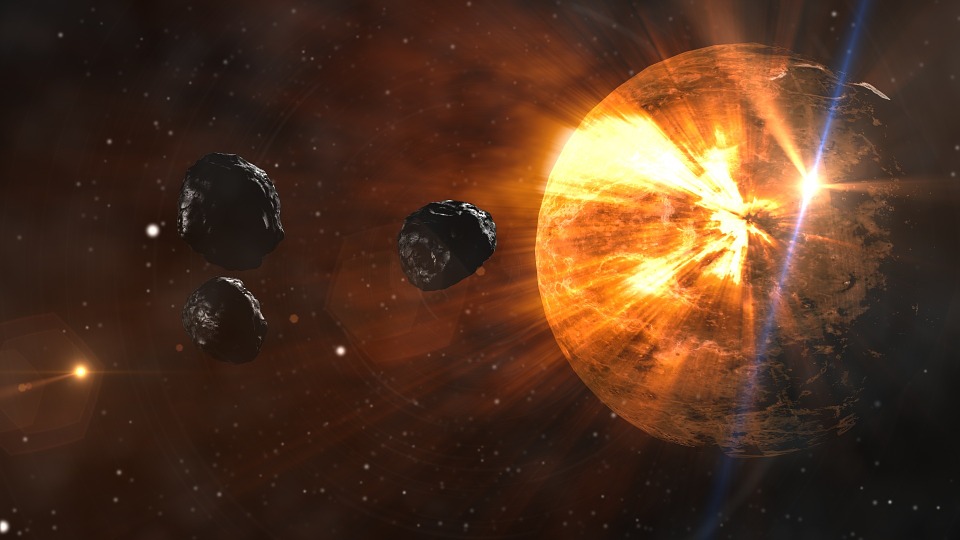

I’ll be the first to admit a romantic relationship with Armageddon. The film, “Independence Day” (1996), was released when I was just entering my teens, and I fell in love with it – not just the aliens, or Goldblum’s rendition of a hot, brilliant cable technician, but stuff blowing up. Big stuff: lots of big, important stuff reduced to ashes by massive walls of fire, spreading across whole cities from a center point like ripples from a gigantic raindrop.

The decimation of entire cities, the focus on striving for salvation as society crumbles into a state of nature, the affirmation of the temporary quality of everything we know – it’s all exciting and engrossing, and it’s not only why disaster movies hold a place in my own heart, but why they tend to do well at the box office. The idea of Armageddon takes the junk out of the way to let the goodness and badness of human nature shine through with uncluttered honesty. Its themes lead to great fiction.

Pro Armageddon Movement

Some people, however, aren’t happy to leave Armageddon up to fiction alone – they take fictional accounts seriously. To someone like me, who knows the Bible’s Revelations to be symbolically confusing but mildly interesting work of fiction written by a mortal man, John of Patmos, this is a very scary order. I’m aware that religions other than Christianity involve their believers in Armageddon stories, but Christianity is the only religion pervasive in my culture, so its affection for the actual end of the world is the one I must address.

Some people, however, aren’t happy to leave Armageddon up to fiction alone – they take fictional accounts seriously. To someone like me, who knows the Bible’s Revelations to be symbolically confusing but mildly interesting work of fiction written by a mortal man, John of Patmos, this is a very scary order. I’m aware that religions other than Christianity involve their believers in Armageddon stories, but Christianity is the only religion pervasive in my culture, so its affection for the actual end of the world is the one I must address.

Sitting in the church as a child, I listened to a sermon on what heaven is like. The predictions of Revelations were included in the talk and, after the service was over, several people were so excited by the ministers’ description of heaven that they “couldn’t wait to go.” Now, since they didn’t commit suicide, I’m sure it’s safe to assume they were exaggerating a little. Since it’s written into the belief system that killing oneself deliberately is a sin, otherwise intellectually healthy Christians aren’t likely to throw themselves before a speeding train any time soon. But that doesn’t mean there’s no need to worry.

Imagine, for a moment, that you have had a job high up in a classified area of government. You show up at work one day to learn that (details aside), a nuclear warhead is headed for your mother’s hometown, on the other side of your country. You have two choices – you can call her and urge her to leave before the evacuation notice is released to the whole city, thus jamming the highways, or you can call her and comfort her with the news that she’ll be going to heaven soon.

What will you do if the whole world is about to end?

If you’re a Revelations-fearing Biblical literalist, you may even believe that the whole world is about to end. After all, one nuke may necessitate a nuclear response. Fortunately for you (and unfortunately for the rest of us), you’re so high up in government that you contribute to the button-pushing decision – you have a say in whether or not the enemy should be nuked back.

You find yourself lifted by an overwhelming sense of purpose, propped up by your belief in predetermination. Obviously, these are the end times, and it’s fallen upon you to help put the inevitable into action. You’re honored to have been put in this place by God – so honored, in fact, that your button-pushing vote is an automatic “yes.” In essence, your belief in the greatness of the end of days halted your prevention of the end of days. Revelation’s prophecies have become self-fulfilling.

Nukes fall. Everyone dies.

It’s an exaggerated example, but at the same time, it exemplifies the kind of thinking that led mostly sane men to fly some planes into some American buildings in 2001. My story was an attempt only to show how unfounded beliefs, especially about the hereafter, can do harm. Belief in being personally rewarded in heaven isn’t as bad as belief in the armageddon, though – the former usually only concerns one’s relationship with herself and her own death. The latter determines one’s treatment of his fellow human beings, and that makes it worrisome.

In other words, I fear pro-Armageddon people because they would shrug their shoulders in the event of the destruction of everything I hold dear. Their main concern is to love and worship an invisible friend, in order to be projected to a fairy land upon their painless death. Most of them aren’t concerned about the non-believers who will suffer as a consequence of God’s wrath. The rest of us had a chance. Because we didn’t worship the person they do, we deserve to suffer until we die and suffer more in hell.

In other words, I fear pro-Armageddon people because they would shrug their shoulders in the event of the destruction of everything I hold dear. Their main concern is to love and worship an invisible friend, in order to be projected to a fairy land upon their painless death. Most of them aren’t concerned about the non-believers who will suffer as a consequence of God’s wrath. The rest of us had a chance. Because we didn’t worship the person they do, we deserve to suffer until we die and suffer more in hell.

I fear pro-Armageddon people because they would be happy to thumb their noses at me in the event of my possible destruction, just because I don’t think the way they think. They don’t only thumb their noses at me, they thumb their noses at the Parthenon, the Louvre, and the Pyramids. The thumb their noses at millions of free thinkers, and billions of people who were, by chance, brought up to believe in a different religion. The thumb their noses at every waterfall, every last copy of Shakespeare’s Hamlet, and every panda bear. They even thumb their noses at one another over silly, trivially differing interpretations of one unclear, archaic tome of totalitarian doctrine.

I fear them because they don’t care about me, no matter how much I might care about them, and if they don’t care about me or what I hold dear, I can’t trust them not to do harm. Their concern for my basic rights is conditional, while my concern for theirs is not. Sure, the dissolution of everything dear to any human being is inevitable, and death is a difficult fact to deal with, but to disrespect the nature of being alive so deeply as to hope to hurry up the process of death – for everyone! – is both disgusting and deeply terrifying.

I’m sure some Armageddon-lovers are happy to claim that I’m only afraid of them because I believe them, and that I’ll be saved just like they are if I open my heart to their god (whatever that even means), and that if I choose not to do this, they aren’t responsible to care what happens to me. I enthusiastically thumb my nose at their ideas – but I don’t thumb my nose at their right to live and be happy.