Seemingly, to answer this question one must draw the division of modern’ and archaic’ Judaism, saying why such a distinction was contrived. This cannot be done in any meaningful way.

The dividing lines between Sadducee and Pharisee

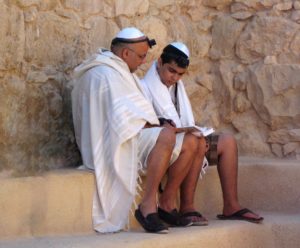

As long as history allows us to see, Judaism has been divided in one way or another and now is no different. The dividing lines between Sadducee and Pharisee in the first century may have been washed away in the sacking of Jerusalem, but echoes of these can be perceived in the divisions common over the last two hundred years. Throughout this paper will run a debate on the nature of modernity that will use Judaism as its battleground. I intend to show how the divisions within Judaism are a natural result of a tradition where multiple interpretations are integral to its scripture (exemplified in the Talmud) and how that process both shaped and was shaped by modernism, rather than simply created by it.

I do not wish to underplay in any way the effect of the Enlightenment on the course of history; however, there seems to be an assumption in lay scholarship that the enlightenment affected all cultures it touched in some radical new way, as though there was a great awakening experienced by all at the same time. It is seen as the spreading of a new, perspective-altering, knowledge that banished ignorance and bigotry like wild-fire over the bone dry bush. This is in the case: it is not as if tradition had never been challenged before.

The Martians did not land and, disguised as serious Germans, introduce the mortals of the earth to their extra-terrestrial, existential angst; the enlightenment came out of the natural evolution of European society and was comprised of pre-existent forms of debate. Similarly, there was no harmony within the Judaic tradition that was suddenly disturbed by maxims such as “Sapere Aude!” and the zeal of a generation freed from the bonds of ignorance by a new confidence in the faculty of reason.

After all, in the second century was there not a debate between Rabbi Akiva and Rabbi Ismael on the nature of the revealed text? Before then, drawn from Hellenistic roots, had there not been the creation of a hermeneutical method that survived in rabbinic scholarship throughout the ages? Is a version of this method now seen as rather cutting-edge by scholars like Paul Ricoeur and Hans-Georg Gadamer?

The vast haul of books retrieved from Constantinople introduced the west to ideas and arts not seen in many years. But it is my contention that what is more important is the language shift that occurred. The discovery and, more importantly, the embracing of so much Latin and Ancient Greek literature has influenced the English language, for one, far more than the original Roman invasion ever did. This is significant in showing the true effect of the enlightenment; that traditional institution was challenged throughout Europe in a language they had no control over.

The vast haul of books retrieved from Constantinople introduced the west to ideas and arts not seen in many years. But it is my contention that what is more important is the language shift that occurred. The discovery and, more importantly, the embracing of so much Latin and Ancient Greek literature has influenced the English language, for one, far more than the original Roman invasion ever did. This is significant in showing the true effect of the enlightenment; that traditional institution was challenged throughout Europe in a language they had no control over.

An interesting analogy is what happened to music; the folk songs that had been taught, learned and played for generations, acquiring new verses and mutating slowly over the course of decades, were overtaken through the enlightenment by a mathematical vocabulary of scales, modal interplay, tension, and resolution. A technical vocabulary that could be used to describe the folk songs of the past, but in doing so left out the years of tradition: music, like beliefs, became objectified. The description, sub specie aeterni, ignored the place or standing in society of the described arts. The use of the language of the enlightenment prompted an apparent explosion of creativity[1] in music and philosophy.

The enlightenment did not, however, come ex nihilo. There had already been an argument raging in the catholic church, dominant in Europe, between the conservatives and the reformers on the question of the interpretation of scripture. Judaism is centered on scripture in an even more fundamental way than Christianity, taking Torah as God’s mandate to the Jewish people.

Galileo and Bellermine Fame

The fame of the case of Galileo and Bellermine would not need to have spread to the Jewish community for there to be similar happenings there. Such commentators as McMullin would argue that the environment being created in Europe would have led inevitably to the clash played out in that famous case; the Jewish community lived in that environment. It would be folly to attempt to decontextualize Jewish history from European history; just as the Jewish hymns of that timeshare melody and form with their catholic neighbors, so did the same revolution of critique, that swept some of the more obese Christian theology aside, find echoes in the Jewish community.

At the time, however, Judaism was without a physical center and was dispersed across Europe, sometimes ghettoised by its host countries. Throughout history, Jews have resisted assimilation while banished from Israel it is by never totally assimilating into host societies that Judaism has survived. Yet the Judaic tradition was gradually changing within itself, too.

Pre-enlightenment development within the Judaic tradition

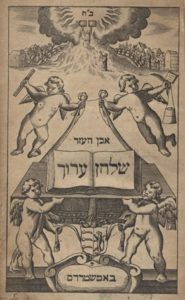

The codification of laws in the Shulhan Arukh (The Laid Table) is an example of a pre-enlightenment development within the Judaic tradition that may well have led to divisions within the community. The compilation of a handier version of the vast and unwieldy oral tradition would have made it more possible for the ordinary Jew to find faults in it, or disagreeable sections that could be improved upon. Before an authoritative codification, one would have to devote one’s whole life to become versed in the content of oral Torah, and thus it was treated with the respect deserving of one’s life’s work. There does seem to be a bubble-gum’ factor here; inasmuch as what was once gained through a lifetime of the study was now available with much greater facility, leading to it being treated with less reverence.

That it seems as though this code was the last great text before the splintering of the rabbinic tradition into reformed, conservative, reconstructive and orthodox Judaism, with all the variants within those categories following with time, may go towards supporting this theory.

That it seems as though this code was the last great text before the splintering of the rabbinic tradition into reformed, conservative, reconstructive and orthodox Judaism, with all the variants within those categories following with time, may go towards supporting this theory.

However, the increasing trend for open debate and criticism of tradition amongst Europeans also must have had an influence upon the Jewish peoples, however, distanced they were, to begin with from the still bigoted establishments. I am putting forward a model, not of modernism sweeping into the Judaic tradition and changing it irrevocably with its new ideas; and not of the Jews, isolated, having their own private revolution. I think it is a case of both/and’ rather than either/or’. The Enlightenment changed Judaism, yes; but Judaism informed the workings of the Enlightenment.

[1] I say apparent’ as this depends on one’s definition of creativity’. In a sense, one only discovers’ mathematics and, in music, the only sound is created’; in which case, there was no more music created in the world than before. For the question of beliefs; the problem is, as I see it, not what form creativity is to take, but whether it is not, in more accurate terms, destruction’. The question put differently could be: Are critics practitioners of an art form (and so can be called creative’), or are they intellectual parasites?’