A conundrum that plagues most modern scholars and Liberal Arts students is whether or not to believe in religion through the teaching of the scriptures, or those of the religious philosophers. This is no more fictional when it comes to the idea of a covenant created between God and the human. One might be inclined to adopt the view of the party most pertinent to them as a human being, which would be that of the Jewish philosopher Martin Buber. The scriptures argue that the covenant between the people and God is a set of rules, a set of standards and a unification of the people. Martin Buber challenges this by explaining that the covenant is the basis of a relationship between divinity and man, man being a sole being, not a people united under the grace and power of God. Therefore, Buber and the writers and editors of the scriptures have somewhat conflicting viewpoints that will be addressed in this essay. Chronologically, one should begin with the scriptures. The scriptures are said to have originated in 70 AD, after the destruction of the second temple in Jerusalem. However, their older existence does not make them superior to the beliefs of Buber, which came much later. They seem to appeal to different groups of thought and have been created for different purposes, all of which will be discussed later in the text. They are mirrored by the fact that they both are covenants that have been manufactured by writers who were trying to inflict a particular belief on a particular society.

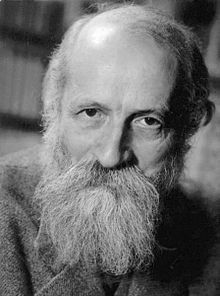

A Jewish philosopher and writer, Martin Buber, did not settle for the traditional and sometimes rigid traditions and restrictions of the Jewish faith. He questioned them and often examined them with more depth than the Jewish community had ever seen (Jones 1055). For instance, he states in the beginning of a speech given to a Jewish assembly that his thoughts regarding the Jewish “law”, in other words, the covenant between the Israelites and God, differ from the ancestral way of thinking (“Foci” 266). This does not exclude from his work any thought and opinion regarding what is in the Bible. He has not nullified the writings of those ancient theologians and scholars who created the scriptures, yet he has gone under the seemingly impenetrable surface and has looked for something deeper to pull it all together spiritually. In doing this, he created his own interpretation regarding what he calls the “real Jew” and the “traditional Jew”(“Foci” 266). These two levels of the Jewish faith which run parallel to each other, are the essence of his analysis of the biblical covenant created by the writers of the scriptures.

A Jewish philosopher and writer, Martin Buber, did not settle for the traditional and sometimes rigid traditions and restrictions of the Jewish faith. He questioned them and often examined them with more depth than the Jewish community had ever seen (Jones 1055). For instance, he states in the beginning of a speech given to a Jewish assembly that his thoughts regarding the Jewish “law”, in other words, the covenant between the Israelites and God, differ from the ancestral way of thinking (“Foci” 266). This does not exclude from his work any thought and opinion regarding what is in the Bible. He has not nullified the writings of those ancient theologians and scholars who created the scriptures, yet he has gone under the seemingly impenetrable surface and has looked for something deeper to pull it all together spiritually. In doing this, he created his own interpretation regarding what he calls the “real Jew” and the “traditional Jew”(“Foci” 266). These two levels of the Jewish faith which run parallel to each other, are the essence of his analysis of the biblical covenant created by the writers of the scriptures.

According to William Hedberg, the core of biblical thought is the covenant (69). This differs from that which lies at the core of Buber’s somewhat humanistic thoughts on the covenant. Buber believes the epicenter of the Jewish faith lies in the relationship between man and divinity. To the untrained ear, this may sound twin-like to the biblical covenant, however, this is not so. The biblical covenant is an agreement between the people of the Jewish nation and God. God will only make the covenant with the people, when they unite as one under the power and glory of their one, true God. The covenant between God and the Israelites is made through Moses. Moses was selected by God, to rescue the Jews from Egypt. “Now, therefore, if ye will obey my voice indeed, and keep my covenant, then ye shall be a peculiar treasure unto me above all people: for all the earth is mine: And ye shall be unto me a kingdom of priests and a holy nation. These are the words which thou shalt speak unto the children of Israel. And Moses came and called for the elders of the people, and laid before their faces all these words which the LORD commanded him And all the people answered together, and said, All that the LORD hath spoken we will do. And Moses returned the words of the people unto the LORD.” (Exodus 19:5-9) Buber does not regard this covenant to be false or even distorted for the benefit of the writers. As Buber is known as the humanist of Judaism, it would make sense that to him the covenant must be made between man and divinity. Within the five books of the Torah, there is no allusion to a relationship between an individual and God. God is always part of the covenant, yet it is partnered with the “people” and not the person (“Judaism”, Buber 216). Therefore, Buber agrees with the idea that a covenant must exist, yet he has his own personal views of who should be a part of it.

Jews and the Covenant

According to the scriptures, the sole people who are a part of this covenant are the Jews.

The scriptural writers decided that they are the chosen people to enter into God’s covenant. Therefore, in order to achieve redemption one must be part of the covenant of the people of Israel. Those in the covenant are to bring more people into it, it is their responsibility. Buber is not in agreement with this. He believes that everyone is in the process of being sanctified; it will eventually take place. No being is completed shunned from this process. The traditional Jews are incapable of understanding the notion of a “massa perdonitis” because their Bible teaches them the idea of exclusive salvation. However, Buber states that when redemption comes, it will be the redemption of the world and not of solely the Jews. God will only redeem when the entire world unites as one (“Foci” 269).

As is stated above, Buber does not believe that the “law” of the Jewish people should be the fundamental part of the Jewish covenant. The biblical covenant is primordially based on law. This law came to the Jewish people at the time of the covenant at Mount Sinai. It was the not first aspect of the Jewish faith, yet it overpowered all other aspects when it came into being (“Foci” 267). The writers of the scriptures decided it was time for the Jews to gather as one people under the power of the divine. Therefore their so-called God came down from his home in the heavens and spoke to His people. Their agreement was based on a set of rules or obligations that His people must obey in order to surrender to the covenant of God (Friedman 5). These Ten Commandments are the scriptural writer’s way of keeping the Jews in line and uniting them. The second example of this would be the Covenant of Circumcision made with Abraham. In this manufactured agreement, Abraham, and all those men who come after him, must sacrifice their foreskin in order to enter unto the grace of their Lord. One can see that all covenants of the Bible, in addition to being between a people and divinity, are based on the obligations of the peoples to their divine being. Buber does not accept the concept of the law being the essence of the Jewish being. In his opinion, the “law” constitutes a third component of the relationship, thus placing an entity between the people and God. The Buber relationship only has room for two beings (Novak 216).

What was Buber’s core interpretation of Judaism?

Buber’s core interpretation of Judaism and religion is the relationship between I and Thou. This is the relationship of which one speaks when explaining the essential part of Buber’s covenant. He moved the understanding of Judaism from being a religion based on stories and ideas to a religion based on the relation (Borowitz 43). This covenant has turned the Buber believing Jews into self-actualizing and autonomous individuals who recognize that their first relationship with God is personal. Those entities who follow the teachings and philosophies of Buber recognize the biblical covenant as part of their history and heritage, not the epitome of their religious beings. They, being part of the people of Israel, one of God’s people, must uphold the laws and traditions of their past. This is what separates the “traditional Jew” from the “real Jew”. The “real Jew” acknowledges that the Bible, which is essentially the most important tool used in proclaiming one’s faith, says that the law, or the covenant, was a primordial encounter with God, but one must look beneath that for a spiritual connection (Borowitz 44). The real Jew must understand that the Sinaitic covenant comes after the inner, spiritual relation with divinity, which is known as the I-Thou relationship.

This I-Thou relationship is the innermost essence of human consciousness; one cannot spiritually live without having the I-Thou relationship. Buber supports this philosophy by comparing it with the idea of living through the experience, which is the I-It relation opposite to the I-Thou. One can experience things and people but these are just mere experiences, not real relations. These connections through experience are limited in the sense that they can only be what man perceives them to be (“I and Thou”, Buber). Experience is based on a notion that is inside of you not between you and the world, therefore one can only experience through oneself with the things around. This would mean that experience is not a real relationship because it does not take a part of that which one is experiencing with, one simply experiences it and moves on. In this sense, neither entities are changed, making the experience a superficial relationship. It is a relation based on the fragments of human beings and objects mixed with their desires and needs. This is essentially the base of an I-It relation; one must have a craving for something or someone in order to experience it. The biblical relation between God and the people of Israel is essentially an I-It because they are only experiencing God through the Bible and the covenant of Sinai, which is a story from the scriptures. This is based on the needs of the people to have a sort of personification of their God, whether or not it comes in the shape of a person. Therefore, these relations are controlled by our senses. According to Buber, this is the one downfall of man and the I-Thou relation. Human beings are limited by their senses, which make us only capable of experiencing other entities (“Foci”, Buber 272). Quintessentially, this is the difference between a direct experience (It) and experimental knowledge (Thou).

This I-Thou relationship is the innermost essence of human consciousness; one cannot spiritually live without having the I-Thou relationship. Buber supports this philosophy by comparing it with the idea of living through the experience, which is the I-It relation opposite to the I-Thou. One can experience things and people but these are just mere experiences, not real relations. These connections through experience are limited in the sense that they can only be what man perceives them to be (“I and Thou”, Buber). Experience is based on a notion that is inside of you not between you and the world, therefore one can only experience through oneself with the things around. This would mean that experience is not a real relationship because it does not take a part of that which one is experiencing with, one simply experiences it and moves on. In this sense, neither entities are changed, making the experience a superficial relationship. It is a relation based on the fragments of human beings and objects mixed with their desires and needs. This is essentially the base of an I-It relation; one must have a craving for something or someone in order to experience it. The biblical relation between God and the people of Israel is essentially an I-It because they are only experiencing God through the Bible and the covenant of Sinai, which is a story from the scriptures. This is based on the needs of the people to have a sort of personification of their God, whether or not it comes in the shape of a person. Therefore, these relations are controlled by our senses. According to Buber, this is the one downfall of man and the I-Thou relation. Human beings are limited by their senses, which make us only capable of experiencing other entities (“Foci”, Buber 272). Quintessentially, this is the difference between a direct experience (It) and experimental knowledge (Thou).

Experimental knowledge is the knowledge that God is there, without really having any proof, which is also the definition of the fear of God. One is aware of his incomprehensibility and omnipresence (“Foci”, Buber 268). This is another branch of Buber’s covenant. His covenant of God with the individual is based on faith and not obligations or demands. This faith is not simply believing that God exists, because this is a given to any Jewish being, yet it is believing that God is always present. This means that no matter what comes to pass, God will always be there, even in the darkest of times (“Foci”, Buber 267). One may not be able to see him or touch him, but that defines the impossibility of having an I-It relationship with divinity. It is the unfeasibility of being able to experience Him with our senses, which enables us to manifest the I-Thou relationship with the eternal Thou. However, in the scriptures, man is made to be able to sense God, by his manifestations to those which he makes his covenants with. Buber however, sees these manifestations as the incentives of those who wrote the scriptures to encourage the following of the people. They induce the act of believing in the covenant by making God seem to be someone who is anthropomorphic and is able to be perceived by the human being. One must, however, look past these stories and recognize their figurative meanings (Freidman 4). They sway the people to believe that their God really does exist and that encourages them to enter into a covenant where they will be protected by this eternally great divinity all while surrendering their complete entity to Him. Yet, these manifestations are manufactured by the scriptural writers, and in essence, are objects, therefore they do not comply with the I-Thou that is necessary to be linked to God, making it impossible to be the real covenant of Judaism.

Buber’s covenantal beliefs also branch out to the dependence of God on man for eternal existence.

In other words, Buber believes that without man, God would not exist, because, in order for him to be a God of the people, the people are necessary. If no one believed in God he would cease to be divine, as one cannot perceive him in any other way than the belief and experimental knowledge, which comes through the I-Thou (“Foci” 268). In the Bible, it is stated that God created man in His image to live on the earth, yet Buber believes that man created God in his own image. Therefore, man is necessary for God to continue to live on in his present state.

Consequently, to achieve Buber’s idea of the real covenant, one must attain the eternal I-Thou relationship. Buber does not abolish the concept of the I-It relationship because it is understood that one must venture through the I-It before one can fully partake in the I-Thou. The two mutually define each other. The I-Thou is the existence of a relationship that has no limits and no predicaments. It is a sacred union in which no man can stand. One takes a stand in relation to the divinity, but one does not become the divinity, nor can anything corrupt the bond between the Thou and the I (Steinberg 57). One cannot be fused with divinity because if the two become one, there is an impossibility of dialogue, and thus the end of existence, as Buber stated that dialogue is the essential part of living. Therefore, there must always be a distance, for the beginning of the I-Thou relationship begins within oneself. The basic movements of this relation are the awareness of each action and each stroke of our own entity. One must not take anything for granted; each breath and each twitch should be taken into awareness and one must know that it is happening but turning it into something perceived and though out. This is an I-It relation. There are two types of awareness that one could achieve. The first being the awareness of the mind, which will not achieve the I-Thou, because one is not feeling what is happening. The second would be the awareness of the body, which will inevitably lead to the I-Thou. One might call it an out of body experience. This takes a secure alignment of the mind, body and psyche to create a mindfulness of one’s own self. This is part of the covenant because it involves surrendering one’s whole self to God, by being aware of everything; one is not simply surrendering our minds, but our entities. This is essentially what the people owe God, according to Buber, for the protection he offers to them in the biblical covenant.

Buber’s covenant is entirely more humanistic and based on the individual autonomy of the Jewish self than the biblical covenant.

They are different in the sense that one is based on laws and one is based on spiritual relations. Buber believes that existence is based on the relationship between God and the divine in the form of the dialogues of life. His beliefs, although from a chronological point of view proceed the biblical covenant, seem to precede it from a spiritual point. This point was proven by his idea of the pre-Sinaitic covenant, which is the relation of the I-Thou, the basis of human-divine co-existence.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TkAlqtJ4Fuo