The Significance of the bDud in Tibetan Buddhism

The Indian subcontinent gave the world one of the most fascinating religions to mankind, Buddhism, and its continual study has allowed people to gain not only insight into their own lives but the lives of others. For scholars, the study of Buddhism remains a focus of anthropological concern, not just because of the inherent interest of the subject matter, but also because Buddhism seems to remain somewhat of a mystery for theories of religion.

Buddhism arose in the 6th century BCE, dedicated to the use and meditative techniques that would aid an individual to escape from the cycle of life, death, and re-birth. Although Buddhism denies the existence of a creator god, they still hold rich mythology; they gave rise to the birth of Buddhas and bodhisattvas (‘Buddha’s-to-be’).

Buddhism arose in the 6th century BCE, dedicated to the use and meditative techniques that would aid an individual to escape from the cycle of life, death, and re-birth. Although Buddhism denies the existence of a creator god, they still hold rich mythology; they gave rise to the birth of Buddhas and bodhisattvas (‘Buddha’s-to-be’).

These individuals helped assimilate Buddhism into the lives of the people who were used to the practice of deity worship. Buddhism also adopted and adapted many Hindu deities to help the new religion flourish. By the 3rd century CE, Buddhism became the dominant religion in Sri Lanka and by the 7th century CE< Buddhist missionaries traveled from India to Tibet.

In Tibet, they came across the indigenous people and the Bon religion, who were, at first, resistant to the new faith. The indigenous religion was characterized by the worship of 2 creator deities who were seen as the principles of good and evil. In addition to this, the Bon religion had a wide variety of lesser deities and had some similarities with shamanism. The Buddhist faith, like with many new religions, incorporated many of the old shamanistic ceremonies into their own practices. This in turn, gave rise to a new form of Buddhism. This is sometimes known as Lamaism from the title ‘Lama’, given to Tibetan Buddhist religious masters or gurus. By the 12th century CE, the Buddhist faith was the principal religion of the area.

The Spirit of bDud

The bDud was one of the many spirits of the indigenous Bon religion that was adopted by the Buddhist faith. They were seen as heavenly spirits by the native people but within Buddhism, they were seen as devils that were said to be black and live in a castle. In China, it was believed that the king of Hor was the demon king of the bDud.

In the festival of Dumje held by the Sherpa’s of Nepal, which is held annually in the spring, figurines of the bDud are used in order to prepare for an elaborate form of masked dancing called ‘cham’, a main feature of the ritual. Dough figurines of the bDud, believed to be demons and of the four directions, are used as paraphernalia. They are modeled with thread crosses, namkha (nam-mkha), fixed in their heads and are sexually unclear. They have prominent breasts but also are decorated with wild animal skins, one leg of which hangs down between their legs in an unquestionably phallic fashion.

Do Spirits produce dreams?

In Tibet, it is believed that the various spirits produce dreams. If an individual dreamt of a snowy mountain or a soaring white bird, it was brought by the lha (deva); if someone dreamt of frogs, snakes, pale-blue skinned or mountain-meadows, then they were illusions created by the klu (nagas); if someone trembles with terror and fear in their sleep, then this is due to the influence of the bdud.

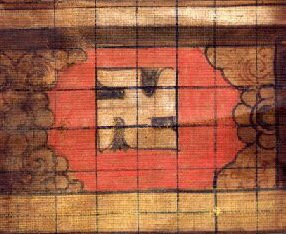

In Tibetan paintings, we can see the bDud playing an important role. The pre-Buddhist supernatural bird, the khyung, a fat-bellied human-like creature with horns, who has claws for feet, wings on his back, a beak for a mouth, and who holds a snake in human-like hands is its basic form. One form of the khyung is that it was the vehicle of the king of the bDud located in the upper spheres.

Throughout the world the history of religions has shown a reoccurring theme; that the dominating religion will inevitably adopt the indigenous deities and adapt them in order to assimilate them into their own religious system. This helps the indigenous people adapt more quickly to the new dominating faith, yet still, retain a hold on their original belief system, and we can see this with the bDud in Tibet’s religious history.

Bibliography:

Paul, Robert A. (1979) Dumje: Paradox and Resolution in Sherpa Ritual Symbolism, American Ethnologist, Blackwell Publishing on behalf of the American Anthropological Association.

Wayman, Alex (1967) Significance of Dreams in India and Tibet, History of Religions, The University of Chicago Press.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gwEdx9YH5_Q