“Travelers, there is no path. Paths are made by walking” – Antonio Machado. Helen Prejean’s life has been a spiritual journey, unexpected and surprising in its twists and turns. She could hardly have known when she entered the covenant, aged 18, that it would take her on this journey. From a relatively sheltered background of wealth and good neighborhoods, Helen Prejean entered death row in Louisiana’s penitentiary. She emerged with a story to tell anyone willing to listen. In many respects, it is not a journey to far-flung lands, but more like discovering what really goes on in your own backyard. The result was the emotionally charged book Dead Man Walking; her account as a witness to Death Row’s inmates; unexplored territory for the majority.

Growing up in Baton Rouge in the 40s and 50s, she saw first hand the laws of segregation. She describes her household as that of ‘The Help’ in terms of having black domestic servants. Her father was a successful lawyer and there was much kindness in her life. She admits she never gave much thought to the racial segregation in the South at that time because she simply didn’t know the hardships it placed on people.

Spiritual awakening

Soon after becoming a member of the congregation of St Joseph, she got her degree, a BA in English and Education. She successfully taught at a private catholic school and says she loved teaching the children. When she reached the age of 40 something changed: it was a spiritual awakening. She realized that the gospel of Jesus was more than just charity. It was more than being kind and not being racist. It was not a gospel of prosperity; Jesus was on the side of the outcast and the poor. This spiritual revelation led her to move to one of the poorest and most violent housing developments of the 1980s, St Thomas Housing Project.

It was another world and not the America she knew. As she worked amongst the people, she began to experience and know poverty. Poverty was uneducated vulnerability, crime, and suffering, heartache, and loneliness. She felt nagging guilt for the privileged wealthy school she had been teaching at when she met people who could barely read. They didn’t even have running water for an extended period of time. People would hold up boards saying ‘No Water’ in protest. Privileged people don’t know they are privileged she says about herself.

It was another world and not the America she knew. As she worked amongst the people, she began to experience and know poverty. Poverty was uneducated vulnerability, crime, and suffering, heartache, and loneliness. She felt nagging guilt for the privileged wealthy school she had been teaching at when she met people who could barely read. They didn’t even have running water for an extended period of time. People would hold up boards saying ‘No Water’ in protest. Privileged people don’t know they are privileged she says about herself.

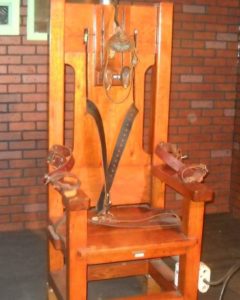

Another unexpected turn of events came about when she was asked to write letters to an inmate on death row. She wrote her first letter to Elmo Patrick Sonnier. He surprised her by replying that he would like for her to visit him. She remembers feeling terrified when she came to the green metal door in the heart of Louisiana State Penitentiary that said ‘DEATH ROW’ above it. She met Patrick for the first time through a heavy mesh screen. He was evidently so thankful that somebody had come to visit him that Helen saw not a monster’s face but a face of humanity. Despite his crimes, he was still human like her. The two hours she spent talking to him flew by. He never once mentioned the rape and murder of Loretta Ann Bourque and her boyfriend David LeBlanc.

Sister Prejean became Patrick Sonnier’s spiritual advisor

Sister Prejean became Patrick Sonnier’s spiritual advisor and remained with him yet still helpless to prevent his execution. On his final day, she stayed with him telling him to watch her face throughout as hers would be the face of Christ to him. The execution over, she left and vomited. She has been the spiritual advisor for 6 men on death row. With no two cases alike, it was her experiences with Dobie Williams and Joseph O’Dell, whom she was convinced were innocent, that set a fire within her. She wrote her second book, The Death of Innocents, to present her case to the public. Now she had intimate knowledge of the inner workings of the death penalty machinery, her work was to bring it to people’s attention. She believes that the only reason it continues to exist is through a lack of public awareness of its intimacies.

Spiritual advisor for the murderer and helping the victims

She admits that when she first got involved with death row it was difficult to know how to reach the families of the murdered victims. How could she stand as a spiritual advisor for the murderer whilst also helping his victims? Despite enormous challenges, she found a way to bridge this gap. Talking to the father of murdered David Leblanc she found that they suffered enormously, not just for the death of a loved one, but through the complex nature of their experiences lasting far beyond the state’s justice system. Many people are just unable to help with such a complex issue that few experiences. She set up ‘Survive’, a support group for families of victims of violence.

What began as simple beginnings, a desire to be a good nun and live by what she believes, she found herself unable to look away from social injustices. Seeking justice for the outcasts of society has become her life work and passion. She says ‘If you become alive for justice and for causes much bigger than yourselves, and work for that, then you begin to feel in your heart that passion that is bigger than just you.’