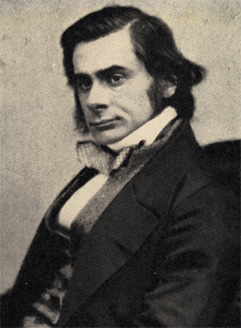

“Validating agnosticism” appears to be a form of fool’s errand on the order of looking for a thousand feet of flight line. The concept of agnosticism is self-validating, particular in terms of the definition created by Thomas H. Huxley. In an essay of 1889, titled “Agnosticism,” Huxley restates his description about generating the neologism he had devised.

“When I reached intellectual maturity and began to ask myself whether I was an atheist, a theist, or a pantheist; a materialist or an idealist; Christian or a freethinker; I found that the more I learned and reflected, the less ready was the answer; until, at last, I came to the conclusion that I had neither art nor part with any of these denominations, except the last. The one thing in which most of these good people were agreed was the one thing in which I differed from them. They were quite sure they had attained a certain “gnosis,”-had, more or less successfully, solved the problem of existence; while I was quite sure I had not, and had a pretty strong conviction that the problem was insoluble. And, with Hume and Kant on my side, I could not think myself presumptuous in holding fast by that opinion.”

The Metaphysical Society

He then describes his joining The Metaphysical Society and discovering that most other members had an “-ist” appended to their primary style of thinking.

“So I took thought, and invented what I conceived to be the appropriate title of ‘agnostic’. It came into my head as suggestively antithetic to the ‘gnostic’ of Church history, who professed to know so much about the very things of which I was ignorant; and I took the earliest opportunity of parading it at our Society. . . . To my great satisfaction, the term took . . . . That is the history of the origin of the terms “agnostic” and “agnosticism. . . .”

Somewhat further on in the essay, Huxley wrote:

“. . . agnostics, they have no creed; and, by the nature of the case, cannot have any. Agnosticism, in fact, is not a creed, but a method, the essence of which lies in the rigorous application of a single principle. That principle is of great antiquity; it is as old as Socrates; as old as the writer who said, “Try all things, hold fast by that which is good” it is the foundation of the Reformation, which simply illustrated the axiom that every man should be able to give a reason for the faith that is in him; it is the great principle of Descartes; it is the fundamental axiom of modern science.

Positively the principle may be expressed: In matters of the intellect, follow your reason as far as it will take you, without regard to any other consideration. And negatively: In matters of the intellect do not pretend that conclusions are certain which are not demonstrated or demonstrable. That I take to be the agnostic faith, which if a man keep whole and undefiled, he shall not be ashamed to look the universe in the face, whatever the future may have in store for him.

Positively the principle may be expressed: In matters of the intellect, follow your reason as far as it will take you, without regard to any other consideration. And negatively: In matters of the intellect do not pretend that conclusions are certain which are not demonstrated or demonstrable. That I take to be the agnostic faith, which if a man keep whole and undefiled, he shall not be ashamed to look the universe in the face, whatever the future may have in store for him.

“The results of the working out of the agnostic principle will vary according to individual knowledge and capacity, and according to the general condition of science. That which is unproven today may be proven by the help of new discoveries tomorrow. The only negative fixed points will be those negations which flow from the demonstrable limitation of our faculties. And the only obligation accepted is to have the mind always open to conviction.”

Huxley’s Definition of Agnostic

Over the 140+ years since Huxley devised his agnostic definition, several different forms of philosophical baggage have been added to the concept. Such things as weak and strong agnostics, believers who acknowledge they cannot “prove” their theism, atheists who concede they cannot prove the non-existence of a god or immortality, etc., and some clever thinkers who hold the agnostic view while waiting for a workable definition (or theory or hypothesis) for the existence of a god which can then be subjected to valid inquiry and testing. Basically, however, all subsequent variations are footnotes to Huxley’s definitions.

An agnostic validates his or her philosophical position by questioning and doubting any “proof” for the existence of a deity and requiring substantive evidence for any assertion that there is a god or gods. When an agnostic asserts “I do not know,” that is its own validation of the concept.